Successful bedside manners might be one of the most important skills a doctor can have. Doctor-patient relationships strongly influence the patient’s health choices, their satisfaction with their doctor, and the potential of them filing a malpractice claim. It’s not something to just brush under the rug during medical school.

Unfortunately, medical experts think that successful bedside manner is in decline. Luckily, a recent study from the University of Michigan and the digital healthcare company Medical Cyberworlds Inc. provides evidence that training with virtual humans could be a great help for doctors-to-be.

The students who used the MPathic-VR had to work through two scenarios. In one them they had to interact with a virtual oncology nurse, upset with an accidental decision the student made. The second scenario featured a distressed patient, to whom the students had to break bad news. After ending the scenario, the students could redo it immediately; making it possible to show what they learned.

###Surgerystudy###

The students had to take the advanced objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) to objectively prove the positive outcomes of MPathic-VR. The students using MPathic-VR achieved significantly higher composite scores on the OSCE than computer-based learning-trained students. They also improved more between their first and second interactions with each scenario.

MPathic-VR seems to be an engaging and effective tool to teach medical students advanced communication skills. The skills also seemed to transfer to a more realistic clinical situation.

Unfortunately, medical experts think that successful bedside manner is in decline. Luckily, a recent study from the University of Michigan and the digital healthcare company Medical Cyberworlds Inc. provides evidence that training with virtual humans could be a great help for doctors-to-be.

Two scenarios

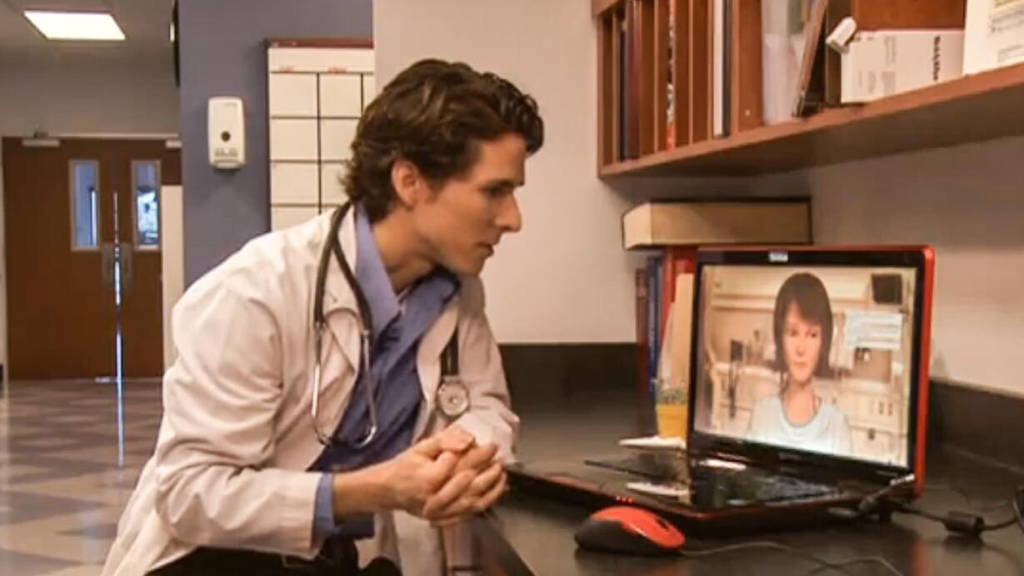

The researchers made use of a virtual human program, named the MPathic-VR. The simulation is designed to understand the students’ voice and body language, and give real-time responses. The computer does so by assessing human body language, facial expressions, and communication strategies. The program, or ‘human’, then responds either positive or negative.The students who used the MPathic-VR had to work through two scenarios. In one them they had to interact with a virtual oncology nurse, upset with an accidental decision the student made. The second scenario featured a distressed patient, to whom the students had to break bad news. After ending the scenario, the students could redo it immediately; making it possible to show what they learned.

###Surgerystudy###

Positive responses objectively proved

The study was conducted among 421 second-year medical students. They would use either the MPathic-VR or a computer based learning module. Of course, the computer based program did not include responsive virtual humans. The students favoured working with MPathic-VR over the computer based learning module. The students valued the immediate feedback, teaching nonverbal communication skills, and preparing them for emotion-charged patient encounters.The students had to take the advanced objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) to objectively prove the positive outcomes of MPathic-VR. The students using MPathic-VR achieved significantly higher composite scores on the OSCE than computer-based learning-trained students. They also improved more between their first and second interactions with each scenario.

MPathic-VR seems to be an engaging and effective tool to teach medical students advanced communication skills. The skills also seemed to transfer to a more realistic clinical situation.