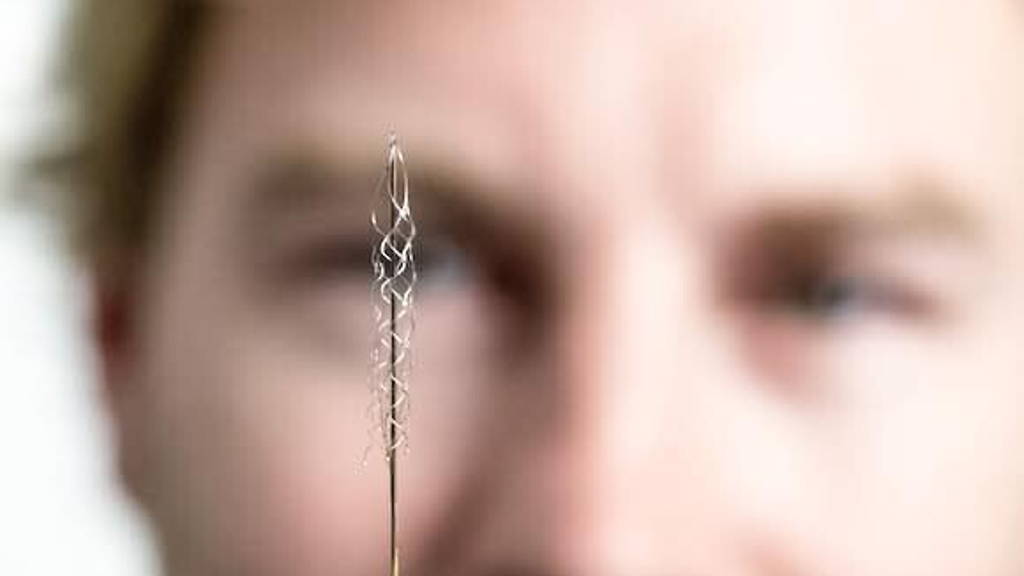

The ‘stentrode’ is placed inside the brain, which on its own isn’t that ground-breaking. Several groups are already researching and developing brain-machine devices. The research team, led by Thomas Oxley from the University of Melbourne, however, has developed a way of implanting electrodes in the brain without opening up the skull.

Each movement a human makes, results in different patterns of brain signals. It’s these signals that the ‘stentrode’ will pick up. Fine wires run from the electrodes down through the blood system, into a recording device implanted in the chest. This device will then wirelessly transmit the information to the exoskeleton.

###stentrode###

Electrodes placed on top of the scalp also do not require surgery, but aren’t as effective, since the signals get muffled by the skull. The ‘stentrode’ avoids both brain surgery and being muffled by the skull. The records aren’t as detailed as those of directly implanted electrodes, but they’re close, according to the researchers.

Detecting brain signals

Their electrodes are placed inside a metallic mash tube, which is then placed inside the brain through a small incision in the jugular vein in the neck. The electrodes measure signals from brain cells from their place in a blood vessel in the brain, along the motor cortex.Each movement a human makes, results in different patterns of brain signals. It’s these signals that the ‘stentrode’ will pick up. Fine wires run from the electrodes down through the blood system, into a recording device implanted in the chest. This device will then wirelessly transmit the information to the exoskeleton.

###stentrode###

No brain surgery

The ‘stentrode’ team was inspired by cardiologists, who use a similar technique. The placement of the device can be done without brain surgery. It also does not require the electrodes to be placed directly inside the brain, which is a positive, since the brain sees electrodes as foreign objects. Over time, it will cover those electrodes with scar tissue, which inhibits their function.Electrodes placed on top of the scalp also do not require surgery, but aren’t as effective, since the signals get muffled by the skull. The ‘stentrode’ avoids both brain surgery and being muffled by the skull. The records aren’t as detailed as those of directly implanted electrodes, but they’re close, according to the researchers.